On March 11, 1862, everyone was thinking about George B. McClellan. Lincoln’s cabinet met and groused about their chronic dissatisfaction with the General. Frustrated with McClellan’s “slows,” Lincoln issued War Order No. 3, which fired McClellan as General-in-Chief but retained him as commander of the Army of the Potomac. He spent the rest of the day explaining his decision. War Order No. 3 stated:

On March 11, 1862, everyone was thinking about George B. McClellan. Lincoln’s cabinet met and groused about their chronic dissatisfaction with the General. Frustrated with McClellan’s “slows,” Lincoln issued War Order No. 3, which fired McClellan as General-in-Chief but retained him as commander of the Army of the Potomac. He spent the rest of the day explaining his decision. War Order No. 3 stated:

Major-General McClellan, having personally taken the field, at the head of the Army of the Potomac, until otherwise ordered, he is relieved from the command of the other military departments, he is retaining command of the Department of the Potomac.

Ordered further: That the two departments now under the respective commands of Generals Halleck and Hunter, together with so much of that under General Buell as lies west of a north and south line indefinitely drawn through Knoxville, Tennessee, be consolidated and designated the Department of the Mississippi; and that, until otherwise ordered, Major-General Halleck have command of said department.

McClellan had been an irritant from the beginning. The embarrassing loss at the first Battle of Bull Run sent Winfield Scott to retirement and left Lincoln desperately searching for a military leader. With few options, he turned to a young George B. McClellan for his next General-in-Chief. The Ohio-born McClellan had exhibited strong leadership in two small skirmishes in western Virginia, and he came highly recommended by Ohio Governor William Dennison and Ohio native Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase.

McClellan masterfully outfitted and drilled his raw recruits into a skilled Army of the Potomac, yet he consistently refused to put them into action. He repeatedly claimed the Confederates vastly outnumbered him, even though he had up to twice as many troops at his disposal. His soldiers loved him, but McClellan’s overabundance of caution led to Lincoln’s significant frustration. Adding insult, McClellan arrogantly considered himself vastly superior to the President, referring to Lincoln in letters home to his wife as “nothing more than a well-meaning baboon” and “a gorilla.”

Peninsula Campaign

Despite his position as General-in-Chief, McClellan rarely communicated his strategy or progress. His insubordination included ignoring the President and retiring to bed after Lincoln had sat patiently in McClellan’s parlor for an hour waiting for him to return from an evening out. Continuing to press his generals to fight, Lincoln suggested that the well-trained army make a frontal assault on Confederate forces between Washington and Richmond. McClellan disagreed, eventually counter-proposing a complicated plan to take the Confederate capital of Richmond from the South, which was in direct opposition to Lincoln’s strategy to defeat armies, not take territory.

After several months of obsessive planning, in March 1862 McClellan began shipping troops down the Potomac River to the Virginia peninsula between the James and York Rivers. The size of the troop movement was unprecedented, with more than 120,000 men, a dozen artillery batteries, and tons of equipment all ferried into place at the base of the peninsula. To Lincoln’s chagrin, further overland movement toward Richmond was painfully slow because of bad weather, mud, and McClellan’s exaggerated opinion of enemy troop strength. The Union forces negated the advantage of surprise, and by the time they advanced toward Richmond the more mobile Confederate army had positioned itself to defend the southern capital. Meanwhile, McClellan, against Lincoln’s wishes, had left the Union capital woefully unprotected.

By any measurement, the Peninsula Campaign was a disaster. The Union survived its critical blunder only because of Lincoln’s strategic decision-making. McClellan, of course, blamed Lincoln for supposedly meddling. A frustrated Lincoln demoted McClellan. This left the president once again in desperate need of a military leader. Generals Henry Halleck, Ambrose Burnside (whose trademark facial hair was the inspiration for the term “sideburns”), Joseph Hooker, John C. Fremont, John McClernand, John Pope, George Meade, and others were all considered by Lincoln but ultimately found wanting. Sitting in the wings were Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, western generals who had not yet captured the president’s eye.

McClellan’s demotion was short-lived. In utter desperation and after several disastrous Union losses in the summer of 1862, Lincoln once again turned to McClellan as his General-in-Chief.

At the time, Lincoln was experiencing personal heartbreak in addition to the pressure of mounting Union soldier casualties. In February, Mary Lincoln had planned a grand open house to show off the dramatic and expensive improvements she had made to the aging and neglected White House. By the night of the party, however, Lincoln’s two youngest sons had become severely ill. While guests gathered downstairs, Lincoln and Mary repeatedly slipped upstairs to check on their ailing children. Diagnosed with what was likely typhoid fever, Willie progressively worsened. On February 20, 1862, he died. Tad recovered, but never really understood the sudden loss of his older brother and constant playmate.

Mary was devastated, and for the rest of her time as First Lady (a term she coined to refer to her position) she wore nothing but black. Relying even more on her trusted confidante, former slave Elizabeth Keckley, Mary became an even greater burden on household staff and the growing list of Washington insiders who despised her. Lincoln mourned as well, coping by throwing himself more deeply into the continued struggle to save the Union. One part of that struggle was the hugely important battle of Antietam.

Antietam

In September 1862, Confederate General Robert E. Lee led his Army of Northern Virginia into western Maryland. Following their victory at a second battle of Bull Run, Lee moved his army north to a point near Sharpsburg, alongside Antietam Creek, where they took up defensive positions. With surprising aggressiveness, McClellan’s Army of the Potomac attacked Lee’s forces on September 17. The first assault came from Union General Joseph Hooker on Lee’s left flank, while General Ambrose Burnside later attacked the right. A surprise counterattack from Confederate General A.P. Hill helped push back Union forces. Eventually, Lee’s troops withdrew from the battlefield first. He moved his remaining army back across the Potomac into the safety of Virginia.

Always overly cautious, McClellan made no effort to follow. Lee had committed all of his 55,000 men, while McClellan only ordered a portion of his larger 87,000-man force into the fray. This numerical imbalance allowed Lee to create and exploit tactical advantages he should not have had. When questioned by Lincoln about his failure to pursue Lee, McClellan complained that his army and horses were sore-tongued and fatigued, and thus required rest. Lincoln responded tersely by telegram:

Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigue anything?

Antietam was destined to be the single bloodiest day of battle in American history. The casualties for both armies totaled a staggering 22,717 dead, wounded, or missing.

Despite Lincoln’s frustration, Antietam stood out as an important battle in the fight for freedom. Although essentially a draw, the fact that Lee withdrew from the battlefield first allowed the North to record Antietam as a victory, something that Lincoln had been needing for some time.

He issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation a few days later.

[Adapted from my book, Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America]

[Image Credit: U.S. Signal Corps/National Archives, Washington, D.C.]

David J. Kent is the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Follow me for updates on my Facebook author page and Goodreads.

On February 2, 1865, Abraham Lincoln headed to Hampton Roads in Virginia for a peace conference. It almost killed the 13th Amendment.

On February 2, 1865, Abraham Lincoln headed to Hampton Roads in Virginia for a peace conference. It almost killed the 13th Amendment. On July 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln presented the draft

On July 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln presented the draft  On May 14, 1841, Abraham Lincoln’s law partnership dissolved when his mentor John T. Stuart was reelected to Congress. Lincoln immediately entered into a new partnership with Stephan T. Logan, the man who had assured his moral fortitude and “good character” when he first became a lawyer.

On May 14, 1841, Abraham Lincoln’s law partnership dissolved when his mentor John T. Stuart was reelected to Congress. Lincoln immediately entered into a new partnership with Stephan T. Logan, the man who had assured his moral fortitude and “good character” when he first became a lawyer. What a year in a writer’s life. I was incredibly busy this year even though I finished no new books. As I look back on

What a year in a writer’s life. I was incredibly busy this year even though I finished no new books. As I look back on  Abraham Lincoln married Mary Todd on November 4, 1842. It came as a surprise to many, possibly even Lincoln himself.

Abraham Lincoln married Mary Todd on November 4, 1842. It came as a surprise to many, possibly even Lincoln himself. On October 18, 1854 Lincoln rose to the forefront of the Republicans with a speech he gave first in Springfield, and then a dozen days later in

On October 18, 1854 Lincoln rose to the forefront of the Republicans with a speech he gave first in Springfield, and then a dozen days later in  On September 27, 1841, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to

On September 27, 1841, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to

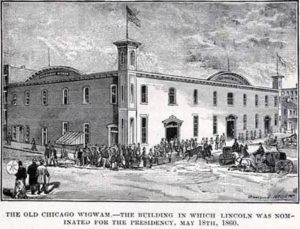

I’m currently chasing Abraham Lincoln’s wigwam, the name given to the building in which Lincoln received the Republican nomination for President in 1860. Here’s the backstory:

I’m currently chasing Abraham Lincoln’s wigwam, the name given to the building in which Lincoln received the Republican nomination for President in 1860. Here’s the backstory: