Union victories were coming more frequently in the late summer and fall of 1863, although not universally, as a loss at Chickamauga and the New York draft riots would attest. But now it was time for a more somber occasion.

Union victories were coming more frequently in the late summer and fall of 1863, although not universally, as a loss at Chickamauga and the New York draft riots would attest. But now it was time for a more somber occasion.

Because so many soldiers had perished during the three-day battle at Gettysburg, a committee was set up to dedicate a cemetery to those who died there. Committee chairman David Wills invited the President to offer “a few appropriate remarks” to “formally set apart these grounds to their sacred use.”

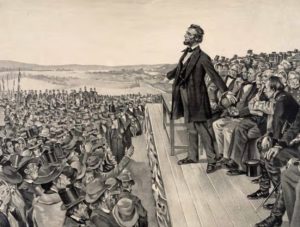

On a chilly November 19, Lincoln addressed the crowd after the oration by keynote speaker Edward Everett. Lincoln sat on the speaker’s platform and listened to an opening prayer, music from the Marine Band, and Everett’s two-hour discourse on “The Battles of Gettysburg.” Following another short hymn sung by the Baltimore Glee Club, Lincoln rose to speak. He finished a mere two minutes later, so fleeting that many in the crowd largely missed his dedicatory remarks.

While Everett’s much longer keynote, resplendent with neo-classical references and nineteenth-century rhetorical style, was well received, generations of elementary school students have memorized Lincoln’s brief address. The irony of Lincoln observing “the world will little note nor long remember what we say here” is not lost on history.

Lincoln’s remarks were designed both to dedicate the cemetery and redefine the objectives of the ongoing Civil War. The “four score and seven years ago” sets the beginning of the United States not at the Constitution, but the 1776 signing of the Declaration of Independence, where “all men are created equal.” Those ideals were under attack, “testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” After honoring the men who “struggled here,” Lincoln reminds everyone still living what our role must be:

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

As he gave his address, Lincoln was already feeling the symptoms of variola, a mild form of smallpox, which kept him bedridden for weeks after his return to Washington. He eventually wrote out several copies of his address, including one sent to Everett to be joined with his own handwritten speech and sold at New York’s Sanitary Commission Fair as a fundraiser for wounded soldiers.

[The above is adapted from my book, Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, available in Barnes and Noble stores now.]

But wait, there’s more. This past year I made several “Chasing Abraham Lincoln” trips, including long road trips to Kentucky/Indiana and Illinois. Check out my Chasing Abraham Lincoln thread and scroll down for stories from the road.

But wait, there’s more. This past year I made several “Chasing Abraham Lincoln” trips, including long road trips to Kentucky/Indiana and Illinois. Check out my Chasing Abraham Lincoln thread and scroll down for stories from the road.

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!